A few days ago, OPEC+ announced that it would consider an oil output cut of more than a million barrels per day next week. In a landscape scattered with high market volatility, Saudi Arabia – the top OPEC+ producer – says that the group could cut production. Obviously a big piece of news, it’s important to understand all the moving parts in the oil and gas industry.

What’s OPEC? The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) is a collective intergovernmental organization of 13 countries, namely Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela. As of today, an estimated 80% (1,242 billion barrels) of the world’s oil reserves are located in OPEC countries, while the U.S. leads the world as the top producer of oil. Saudi Arabia and Russia, along with the U.S., remain the top three oil producers, with around 43% of the world’s oil production coming from those countries – more than the rest of the top 10 combined.

The produced crude oil can fall into four main types:

Very light oils – very volatile (vaporization), quickly evaporating while evaporating toxicity levels (harm for environment)

Light oils – moderately volatile and toxic

Medium oils – most common, low volatility, and higher viscosity (resistance to flow/difficulty of refinery), leading to higher toxicity

Heavy fuel oils – most viscous, least volatile, most toxic

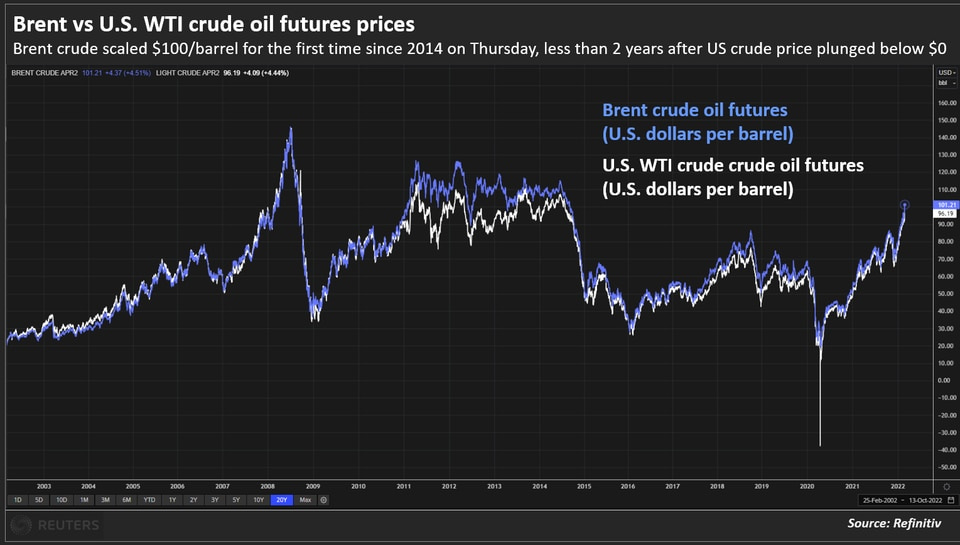

Regarding the crude oil spot market, however, Brent North Sea crude or “Brent Crude” and West Texas Intermediate or “WTI” are the two most heavily-traded benchmark grades – Brent is considered light and sweet (low sulfur content), WTI is considered very light and very sweet. In the futures market, Brent – more attractive because it’s waterborne – and WTI – less attractive because it's landlocked – have historically tracked each other pretty consistently, with a “quality spread” causing Brent to be higher. The CME Group outlines four main fundamental drivers of the spread:

US crude oil production levels

Crude oil supply and demand balance in the US

North Sea crude oil operations

Geopolitical issues in the International crude oil market

In regards to crude oil prices in general, in which Brent and WTI crude typically move together, supply and demand causes prices to change.

Oil Over the Pandemic

The WHO initially reported the coronavirus on the last day of 2019, having an almost immediate impact on oil prices. In January 2020, oil demand from China began falling due to pandemic-related closures, with the country’s demand decreasing by 3 million barrels a day or 20% of the country’s overall oil consumption. As the pandemic continued to spread, Saudi Arabia urged fellow OPEC members and Russia to cut production, but had the opposite effect: OPEC raising output by 1.7 million barrels per day in April at the same time the IEA estimated that global demand for oil was down by almost 30 million barrels per day. Per the laws of supply and demand, prices dropped quickly, with the Producer Price Index for crude petroleum falling 71% from January to April. In April of 2020, the price of oil flipped negative, meaning that a seller would have to pay a buyer $30 dollars per barrel of oil. In the same month, OPEC+ members, along with Russia, agreed to record production cuts of 9.7 million barrels per day through June, the largest cut ever. By May, as businesses started partially reopening across the globe, demand for petroleum showed signs of a rebound. In June, producer prices rose 74%, but recovery slowed as Covid-19 cases resurfaced and travel restrictions continued.

In relation to crude, one of the most interesting continuations of impacts was the large price fluctuations for refined petroleum products – jet fuel, diesel, gasoline – during the pandemic. Fuel demand fell to record levels due to voluntary consumer choices, stay-at-home orders, and international restrictions, but also because of the OPEC-Russia price war that led to crude oil oversupply. The reversal of prices are attributable to three main factors:

OPEC+ limiting crude production

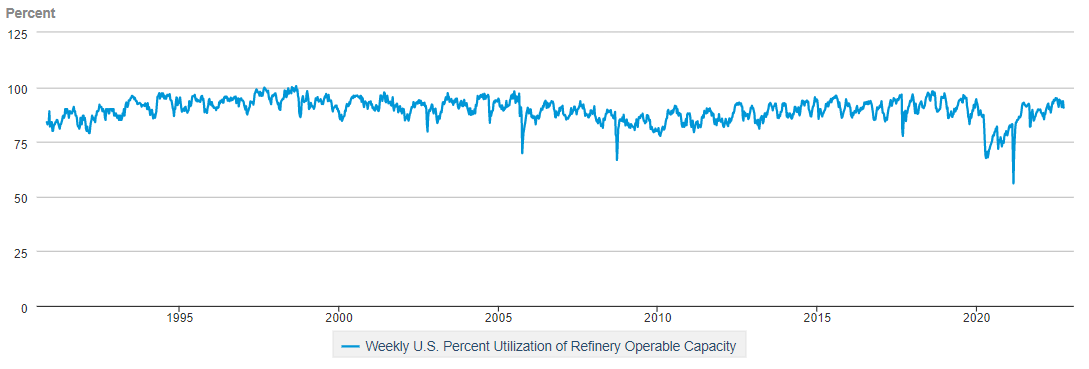

Refiners reducting production capacity utilization rates

Demand rising due to eased restrictions

While these three drivers were instrumental in helping refined petroleum product prices, it’s interesting to see how the same things are affecting oil in the status quo.

Re-de-fining Oil

Peaking earlier this year, crude oil prices have steadily fallen as lower global economic growth is projected, meaning less demand for oil. This decreased demand and the moderately increasing supply of oil has made prices cool off. Recently, OPEC+ put a price floor for Brent at $90 a barrel. In light of this, the announcement of OPEC’s oil output cut makes sense – especially as the price of Brent approaches that floor because of a poor macroeconomic outlook. Also interesting is the status of oil refinery. In the U.S., after more than two decades of growth and becoming the world’s largest refiner by volume, the industry has contracted severely, losing 1.1 million barrels of daily refinery capacity over the pandemic. I mentioned Brent and WTI crude, but both have no utilitarian value until run through a refinery to get processed into fuels, clearly explaining why a strong energy market and a strong refinery sector go hand-in-hand. At the same time U.S. refinery capacity is shrinking, the world lost a total of 3.3 million barrels of daily refining capacity. Why is this happening?

Covid played a big role. The decreased demand of oil reduced the need to keep large oil refineries up and running with low utilization rates. As shown below, refinery utilization fell to record levels over the pandemic, with the rates increasing mostly due to reduced capacity.

The pandemic wasn’t the only factor though. It’s first important to understand that oil refining is not affected by knee-jerk reactions in response to news. The long term nature of refining is based on present and projected fuel demand, political environments, and market access, but also by the relatively irreversible nature of closing down refineries – facility closures are never intended to be undone. In the past couple of years, as refineries in the U.S. began closing, many have been already dismantled or are in the process of being transitioned to full-time renewable fuel production. Even for the ones that haven’t, reopening a refinery is extremely difficult, requiring significant lead time for permits and inspections, rehiring staff, and reintegration with supply chains. The diminishing capacity has had some substantial side effects. Early this summer, Shell saw its refining profits nearly tripled, adding $1 billion to the oil giant’s bottom line because the limited supply of refineries directly related to their pricing power.

Another factor in refinery count reduction are the political and economic pressures against the oil industry as a whole. In August of this year, the House of Representatives approved the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 which includes about $370 billion in clean energy and climate investments over the next 10 years. As the largest piece of climate legislation in history, the Inflation Reduction Act includes tax credits, incentives, and other provisions that are intended to help companies increase investments in renewable energy and enhance energy efficiency. While impactful, the bill is pretty ironic when considering Biden’s stance on increasing OPEC production in the short term.

Fueling the Future

In relation to the future of oil and gas, there are a couple of perspectives of approach. In private equity, there has been a clear distinction of two approaches to transitioning to sustainability in energy. The playbooks of many of the largest buyout firms have adjusted in the past months – mostly pushed by pressure from managers to stop backing producers of fossil fuels and invest more into cleaner energy sources. Of the largest firms, investments into the energy sector can be grouped into one that involves halting investment or even divestment in the industry or remaining invested to transform traditional energy producers. In the first camp, Blackstone has said that neither of its energy businesses will make new investments into oil and gas exploration and production. Likewise, roughly 1,500 institutions including pension funds, educational institutions, and others have also pledged to divest from fossil fuels. The second camp seems to be more popular in PE, and reasonably so. KKR hasn’t formally announced its stance, but the firm hasn’t invested in a traditional energy company in years. However, the firm still continues to buy and manage oil and gas assets through Crescent Energy, though the company is focused on making businesses more climate-friendly and isn’t developing any new oil or gas fields. Carlyle and Brookfield also share the same approach, arguing that PE firms should use their capital to transform traditional energy producers from the inside due to their importance to the global economy.

The significance of traditional energy producers is increasingly present from a global dependency perspective. I referenced the Unburnable Wealth of Nations published by the International Monetary Fund in a previous post:

“[Developing] nations face three special challenges. First, they have a higher proportion of their national wealth at risk than do wealthier countries and on average more years of reserves than major oil and gas companies. Second, they have limited ability to diversify their economies and sources of government revenues—and it would take them longer to do so than countries less dependent on fossil fuel deposits. Last, economic and political forces in many of these countries create pressure to invest in industries, national companies, and projects based on fossil fuels—in essence doubling down on the risk and exacerbating the ultimate consequences of a decline in demand for their natural resources.”

An order of events in a sequenced closure of the world’s fossil fuel industry would be potentially catastrophic from developing, low-income countries where a high percentage of their economic function relies on fossil fuels. One solution that follows the second private equity playbook, inturn recognizing the economic reliance on traditional energy companies, is the implementation of carbon pricing.

Carbon pricing is an instrument that captures the external costs of greenhouse gas emissions and is used as a mechanism to harness market forces to incentivize companies to lower their emissions. The underlying aspect of carbon pricing strategy is the idea of “polluter pays”, holding companies responsible for environmental and social costs of greenhouse gas emissions. There are two types of carbon pricing: carbon tax and emissions trading schemes (ETS). Carbon tax sets an exact price on carbon by specifying a tax rate on emissions or carbon amount found in fossil fuels. ETS works by limiting or capping the allowed amount of greenhouse gas emissions and lets market forces arrive at the carbon price. The two are essentially direct inverse of one another in terms of amount of emissions and the price of carbon.

There are pros and cons for both pricing models, but carbon tax is arguably more impactful. Enforcing a simple tax is a lot more feasible because of the tax collection mechanisms already in place. Also, a carbon tax provides price certainty and stability that give the government consistent revenue to either offset other taxes or reinvest into alternative fuel industries. The structure is also shielded from market volatility, potential loopholes, and market gaming/speculation. Regardless, I think that a carbon pricing model has more potential than the carbon credit market because it holds polluters accountable for emissions rather than giving them a way out of emissions reduction – here are more of my thoughts on carbon credits. I’ll end with a quantitative explanation of carbon pricing’s effectiveness from McKinsey. In their model, with a carbon price of $100/ton CO₂e. the percentage of oil projects that break-even at $60 per barrel falls from 90% to 80% and the percentage of projects that break-even with commodity prices below $30 per barrel falls from 25% to less than 20%. Essentially, this demonstrates an increased incentive for companies to rationalize their most carbon-intensive assets and increase their carbon emission efficiency.