A (Long) Brain Dump on Investment Banking Recruiting

Marking the end of a chapter

I recently concluded what has probably been the weirdest, most stressful, and most emotionally-confusing period of my life. For my non-banker readers (hopefully most of y’all), the year-long roller coaster I’ve just gotten off of was the investment banking recruitment process. Thinking about it now, this chapter in my life might’ve been the most important one thus far, so I wanted to give a lengthy reflection on my experiences.

I don’t have much of an end goal with this piece and it’s largely just a pent-up brain dump of thoughts I’ve had throughout the process, but I’d love for this to be helpful to anyone going through a major transitory phase in their life. Another thing worth mentioning is that I definitely don’t want this to be grouped together with “college freshman starting a college application consulting business after getting into an Ivy League” nor with this guy. I’ve structured this post to be a roughly chronological timeline of the past two years with some lessons I’ve learned scattered throughout. With that being said, this brain dump has a number of long tangents and anecdotes that could definitely have been split up into different posts. Still, I hope you enjoy!

Background

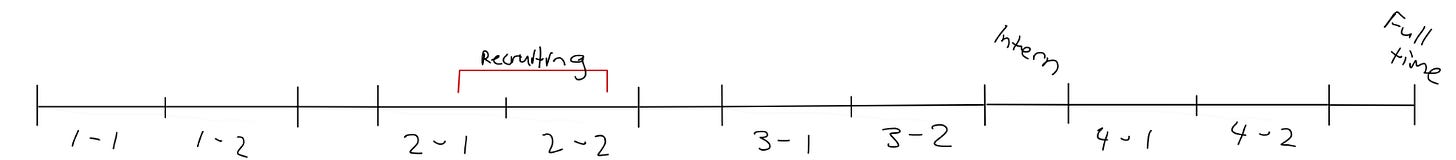

The investment banking recruiting process, at risk of being redundant, is odd – even more so in hindsight. For a junior summer internship (which interns pray end up in a full-time offer), the networking and interviewing happen sophomore year. In the context of a four-year college timeline, here’s what that looks like:

The year-and-a-half gap between recruiting and internship pales in comparison to the years of other steps that precede it. To sum it up, the following is a way-too-long overview of my experience recruiting investment banking out of a large state business school starting back at Poolesville High School – home of the Falcons.

High School: The Butterfly Effect Catalyst

Applying to college – years before I’d ever heard the terms “merger” or “acquisition” – was the earliest point in time that I can reasonably attribute a good amount of importance to. Prior to IB recruitment, applying to colleges probably topped the list of the most stressful periods of time in my life. This is actually something I think is pretty widespread among high school students from middle-class suburban neighborhoods – we dive into this a little more in episode 13 of Minimally Edited. Anyway, looking back on college applications, there were two main things that translate to success in the investment banking recruiting process.

First, is developing a story. My younger brother is currently going through the college application process, so, amidst proofreading personal essays, I looked back at some of the essays that I submitted. Honestly, based on some of my past writing, I’m not surprised that I didn’t get into my top choices. What my essays needed, and what I think makes a good essay in general, was a strong narrative. The largest parallel in both the college application process and investment banking recruiting process stems from getting someone – admissions officer or banking interviewer – to like you. To do so, the most important thing that you can do is to develop a unique, intriguing story, something that most first gain exposure to when writing college essays.

Second, and I think more importantly, is where you ended up picking to go to school. I always knew that I wanted to go into business, particularly finance. Why? I’m not 100% sure, but it was likely the combination of my dad’s career in finance, a general distaste toward other subjects, and my overarching love for talking to people. Regardless, I pooled my college applications into two camps: good business schools or strong economics programs. Coming from an Asian household, I’ve always had an idea of why the school you go to matters, but it wasn’t until IB recruitment that I realized to what extent.

In the context of investment banking, schools are divided up into three sections based on their relationships with various firms: target, semi-target, and non-target. Texas, not to toot our own (long)horn, falls in the second camp with a pretty large, growing presence on the street. Still, something I noticed throughout the recruiting process was the ridiculously high number of bankers that came from a small number of target schools, largely a derivative of reserved target school interview spots. So, while a school’s banking pipeline might not cross the mind of a high schooler, it has the potential to play a surprisingly massive role in the recruiting process down the line – a somewhat butterfly effect. Simply put, the school you go to matters.

College: The Best Four Years of Your Life?

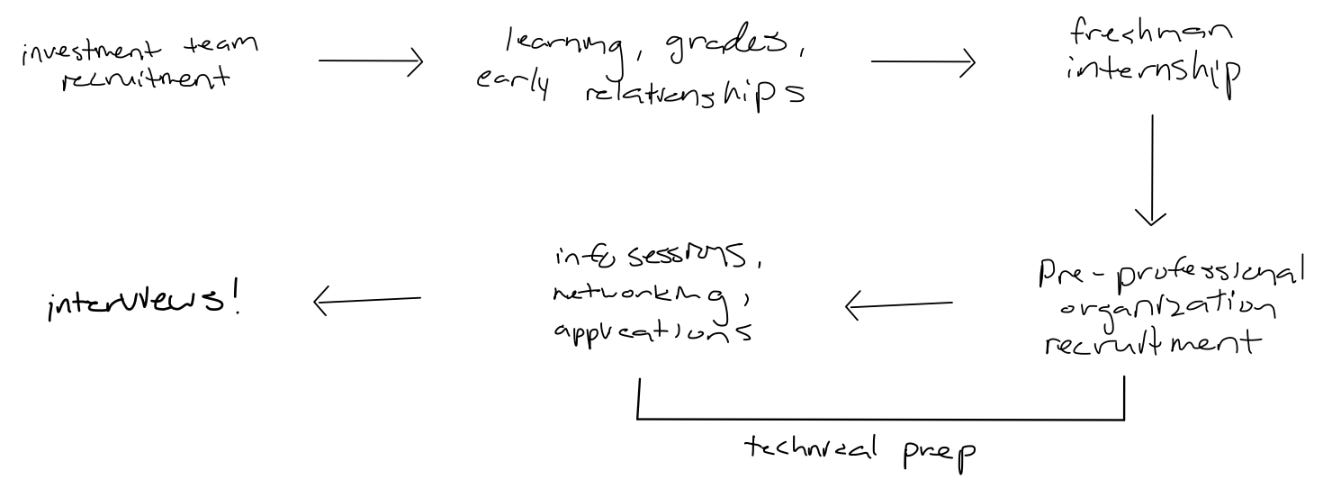

The road to banking began prior to me even knowing what career I wanted to pursue. While the path that I took might’ve varied from others, the steps were logically sequential in hindsight – though it seemed like a complete blur during. This is the cumulation of two years worth of steps and the subsequent lessons I’ve learned along the way:

1. Investment Team Recruitment

Everything started a couple of weeks into my freshman year. As an out-of-state kid (10% of UT), I could immediately tell that there were a few built-in pieces of knowledge that came with going to high school in the great state of Texas – Greek life rankings, impressions associated with certain Texas high schools, familiarity with Texas sports. In relation to finance, there were two stand-out benefits of living in Texas: knowing upperclassmen within finance circles and having a grasp of investment team recruiting.

As a quick primer into the finance community at UT, there are just under 10 main finance organizations on campus. Like most other things, there is “clout” associated with certain clubs, based on things like difficulty of acceptance, alumni network, and curriculum rigor. At their core, however, most of these organizations do the same thing – stock pitches, current market reports, technical preparation, etc.

The way I stumbled into this world can best be defined as a stroke of luck or the grace of God. The day before classes started my freshman year, I showed up to McCombs Kickoff, an event dedicated to integrating new business students into the school. We were split off into groups with two current students leading a smaller group of around 10 and started the event with a series of quick introductions. From there, we received a tour of the business school, sat through a panel of upperclassmen of different majors speaking on their experiences, and met a number of our future professors. After a couple of hours, we concluded with a quick lunch – here’s where the Lord had my back. One of my group leaders, Ishika, struck up a conversation with me, remembering that I had mentioned that I had wanted to pursue finance, and told me about how recruitment for investment teams at UT worked – information sessions, coffee chats, interviews. I ended up grabbing coffee with her before applying to, and ultimately joining, her team – the Texas Undergraduate Investment Team (TUIT).

Increasing your luck surface area

“Then there’s luck that comes through persistence, hard work, hustle, motion. Which is when you’re running around creating lots of opportunities, you’re generating a lot of energy, you’re doing a lot of things, lots of things will get stirred up in the dust.”

The luck razor states that if you’re faced with two equal options, pick the one that feels like it will produce the most luck down the line. A similar perspective comes from Dr. James H. Austin in Chase, Chance, and Creativity: The Lucky Art of Novelty with the four types of luck – this is a good summary. The second type refers to luck that comes from motion, similar to what Naval says in the above quote. Both ideas focus on expanding one’s luck surface area, something I’ve been able to experience over the past two years – particularly with getting into TUIT.

Freshman year Josh wasn’t someone you’d expect to get into one of the top investment clubs at UT. Connections? Didn’t know anyone. Cracked? Far from it. The one thing that I maybe had going for me was my love for talking – though many times it was definitely quantity over quality of content. My initial introduction to finance at UT probably falls into Dr. Austin’s first type of luck: dumb luck. Sure, I had to actually show up to the event, but if I had been assigned to any other group leader, I have no doubt that the rest of my experience at UT would have been extremely different. That being said, the luck that came with being selected as one of five from a pool of almost 100 different applicants was type two: luck from motion.

Dumb luck might’ve been the catalyst for my road to banking, but the rest of my luck down the line was manufactured to some extent. Reaching out and grabbing coffee with Ishika most likely severely boosted my chances of landing an interview for TUIT in the first place. She also connected me with a number of her friends, and it was through conversations with them that I gathered bits and pieces of information about the TUIT interview. In hindsight, this is something that proved to be extremely helpful for two main topics: current events and brain teasers.

The night before my interview, I called my dad, asking about different market events that he was following. He taught me about the dual mandate of the Fed and the recent quantitative easing – guess what I was asked about in the interview. My first exposure to brain teasers came 30 minutes before the interview. I remembered that one of Ishika’s friends had mentioned that they might be asked during the interview, so I quickly looked over a list of questions. Two of the ones I got asked were from that list – it’s a lot easier to solve them when you know the answer.

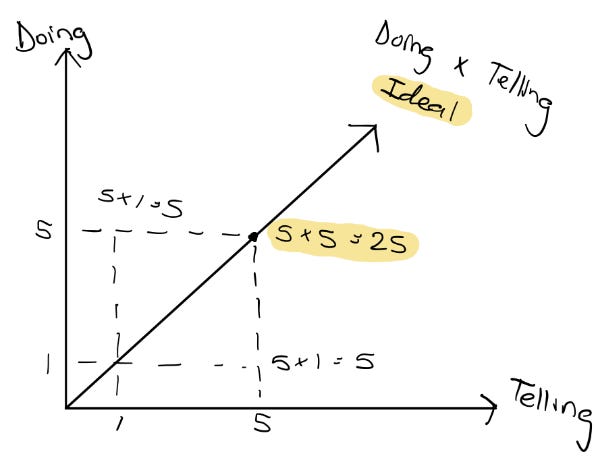

Looking back, applying to TUIT was probably the first time where I’ve been able to see a tangible benefit from expanding my luck surface area, even if that wasn’t a conscious goal at the time. Jason Roberts, in a 2010 blog post, first coined the term, taking a much more formulaic approach. His equation was Luck = Doing x Telling with “doing” referring to working toward your passion and “telling” referring to communicating your passions to others. You can also plot it along a chart:

The big takeaway is that the greatest chance of luck occurs from an equal mixture of both doing and telling. At the same time, however, a lack of either drastically diminishes your luck surface area (25 vs. 5). I think what’s usually preached to most is the doing part – the idea that if you work hard good things will come your way. This causes the telling part to become severely underrated. Notifying those around you when you have your sights set on something can yield huge benefits, just like how Ishika and friends helped me with the TUIT process.

As a second-generation Asian American, I’ve noticed that this conflicts directly with how I was raised. The mentality of your work will speak for itself is ingrained in Asian culture. As a result, looking at my own Asian parents and their friends, it isn’t difficult to notice the lack of self-advocacy within the workplace – a glanced-over definer of the immigrant experience. From stories, it seems like immigrants are often content with waiting for promotions and raises that stem purely from their quality of work, even if said promotions and raises could come earlier.

“The reason is that when people become aware of your expertise, some percentage of them will take action to capture that value, but quite often it will be in a way you would never have predicted.”

– Jason Roberts

2. Learning, Grades, Early Relationships

Joining TUIT was probably the most influential thing I’ve done in my college life – largely because of this section. If the past two years of my life had to be developed into a movie, this part, basically my entire freshman year, would be the training arc – on par with Rock Lee’s in Naruto and the “I’ll Make a Man Out of You” arc in Mulan. The vast majority of time working was spent learning what exactly finance was, grinding out countless market reports, and maintaining a good-enough GPA.

It’s hard to pinpoint specifics of what makes TUIT so special, but I think it really comes down to the investment of upperclassmen into freshmen. The learning experiences, mentorship, and just overall camaraderie within the organization all stem from the involvement and commitment that the juniors and seniors have – something even more impressive when you consider that most upperclassmen already have jobs set up and no real incentive to give back. I’ve been involved in a few other clubs on campus, and it’s easy to tell that the biggest differentiator of TUIT is in the upperclassmen buy-in department.

The value of these relationships and investments wasn’t fully apparent to me until post-recruitment. As such, a very underrated piece of advice for freshmen wanting to recruit IB is building relationships with upperclassmen – especially with seniors. I mentioned earlier that the process is very logically sequential. Still, at every step along the way, relationships with upperclassmen push you forward and give you a leg up. This leads me to the next step.

3. Freshman Internship

I’ve heard many varying opinions about the importance of a freshman internship, the majority of which fall under two camps: (a) freshman internships are unnecessary and you’re better off enjoying your last summer free doing something else like studying abroad and (b) freshman internships are useful in giving you an advantage during sophomore year recruitment. Personally, I fall under the latter. While landing an internship freshman year isn’t the end all be all, it’s definitely a huge plus.

From the beginning of my second semester freshman year to the end of my first semester sophomore year, I worked at a private equity roll-up firm based out of Austin. Landing this internship was the perfect intersection of luck surface area and upperclassmen relationships. In the doing x telling equation, the doing portion came from seeking out an internship and researching what older students had done in the past. The telling portion fell under the upperclassmen relationships that I had built through TUIT. Hidden under the investing side of TUIT were a series of internship “pipelines” – jobs like mine that were passed down from generation to generation. Somehow, my luck had brought me into TUIT where verbalizing my interests led me to a job.

The gig I had landed was probably the perfect freshman internship – a cross-section of money, learning experiences, and, best of all, being completely virtual. I could work whenever and wherever I wanted to, something I made the most out of. Here’s a short list of my favorite internship memories:

Building a valuation model at Yard House happy hour.

Taking calls on a road trip from Maryland to New York.

Responding to emails in between pick-up basketball games at the gym.

Teams messaging my supervisor in between workout sets at the gym.

Working out of a University of Maryland Satellite campus the entire summer.

Working out of Lisbon, Portugal for two weeks – the 9-to-5 becomes a 3-to-11.

It also wasn’t just a waste of time. In nearly every interview since, I’ve spoken about this internship – leaving out the fun parts of course. A good freshman internship gives you learning opportunities and a real world working experience to talk about in the future. Plus, the money’s nice.

4. Pre-Professional Organization Recruitment

Your first year in college should be spent going out, meeting friends, setting yourself up for recruiting, building initial relationships, and working an internship. Sophomore year is where the real fun begins. After hearing a fair share of trauma-inducing stories from upperclassmen, you’re finally ready to begin recruiting – starting with pre-professional organization recruitment. This is something that might be unique to certain schools, but getting into these organizations is pretty important.

The recruiting process for these organizations is sort of circular. To get in, you’ll need to prepare for both technical and behavioral questions, which sounds counter-intuitive when one of the main points of the organization is to learn those same topics. My interviews for these organizations were probably more difficult than the ones for banks. On top of that, the standard for applicants also varies a ton. Those with a so-called “finance background” – dubious after one year in college – are held to higher requirements. Despite raised expectations, however, the same individuals likely have friends on the selection team, infinitely boosting your banking draft stock. This is where my perspective on nepotism stems from.

If you’ve stepped foot into an undergraduate business school, you’ve probably seen students comparing LinkedIn connections and throwing around corny phrases like “your network is your net-worth” or “it’s not about what you know, it’s about who you know”. I love making fun of business students like myself as much as the next person, but they’re kind of right. On top of being technically strong and sounding intelligent, having someone rallying behind you on the inside can have an infinitely larger impact. Especially in the context of investment banking, where the work isn’t too intellectually difficult, this makes a lot of sense. Given that the work product across candidates will probably be relatively similar, people would much rather work with those they get along with – which an internal referral is an excellent proxy for.

So, investment team? Check. Freshman Internship? Check. Upperclassmen relationships? Check. Pre-professional orgs? Hopefully, check. The next part is what the majority of those aforementioned “trauma-inducing stories” refer to.

5. Info sessions, Networking, Applications

Finally, the meat of recruiting. Per the subtitle, this section consists of three main parts. Information sessions are how banks increase their applicant pools, with a select few noting attendance as a way to gauge applicant interest. Networking – taking calls, grabbing coffee – is probably the most time-consuming, important, and subjective part of the process. Applications are usually super straightforward, consisting of personal information and the occasional cover letter – just keep track of deadlines. To prevent this from turning into an investment banking recruiting handbook, I want to dive into my two biggest takeaways from this part of recruiting: crafting a conversation and “the friends I made along the way”.

What Makes a Good Conversation

I mentioned the importance of having someone pulling for you on the inside in the previous section. Networking is how that occurs. By no means am I some sort of expert conversationalist, but I’ve thought about this subject a good amount. How can you formulate a good conversation?

Most people that I’ve talked to agree that strong calls matter, leading to a plethora of regurgitated networking advice. To save you time, here are the main ones I’ve heard: try to talk about things outside of finance, take notes, ask follow-up questions, and don’t be too formal or informal. While important, these aren’t too helpful to think about during an actual conversation.

If you play golf, you’ve probably heard of the term swing thoughts – easily digestible thoughts to remember during various parts of the golf swing. It’s easy to over-complicate every nuance of the swing. Closed face during takeaway, don’t sway hips, keep head still, straight left arm, flat wrist a top, hit down on the ball, forward shaft lean, follow through. The key here is to make them simple. Lead with shoulders, fire hips. With that overly long tangent, here’s the main idea: develop swing thoughts for conversations.

An idea that I dove into with a good friend and informal mentor of mine, Kevin, was the comparison of a conversation to branches of a tree. In a tree, some branches are longer, thicker, and more continuous than others, similar to how certain topics brought up in a call yield longer, more in-depth conversations than others. The swing thought here is find the best branch. A good way to keep track of this is a form of note-taking that Kevin also put me on. It’s simple and involves jotting down short phrases that the other person talks about. From there, it’s about identifying which phrases are the best branches and following up on those.

Another interesting perspective on networking comes from my good friend, Anna, whose friend, a current analyst, noticed a distinct difference in networking calls that came from Asian versus White applicants. Asian students sounded more formal and “by-the-book” while White students were described as energetic and “pushing the boundaries of formality”, noted after one student questioned the validity of a psychology major on a call. Though it wasn’t explicitly mentioned which conversation style was preferred, I’d hypothesize that the preference would lean toward the latter, despite pushing the boundary of professionalism. In the context of networking, excitement, personability, and extroversion are preferred over just professionalism and polish. Most candidates are given the benefit of the doubt – especially from older people – making it difficult to “come on too strong”. Here’s the swing thought: be more excited.

Trauma Bonding?

This “the friends I made along the way” part is a lot less advice heavy. More than just a job offer, the best part of the recruiting process was strengthening my relationships with friends, something best defined as trauma bonding.

After subsequently learning that trauma bonding refers to when a person experiencing abuse develops an unhealthy attachment to their abuser, I realize that I wrongly used the term. As a rebuttal, I’d now like to offer a separate colloquial definition: when individuals deepen their relationship with one another through a shared traumatic experience. I’m aware I used the word in its own definition, but my main idea still stands.

My first experience with trauma bonding comes from competitive swimming. While partly a result of our shared quantity of time in the pool, I strongly believe that the reason my teammates and I were so close was because of our shared swim trauma. We saw each other at the highest of highs when personal bests were broken and the lowest of lows when getting yelled at after a hard practice.

Banking recruiting was extraordinarily similar. At the highest of highs when one of us would get an offer, our small group of friends dropped everything to celebrate. At the lowest of lows when stress levels were at their peak and miniature panic attacks ensued, we were there for one another. It’s difficult to put into words how recruiting changed our friendship, but there seems to be an underlying feeling of respect and care that came out of it.

With that being said, there are two additional points that I want to bring up. The first involves my gratefulness for having this group of finance friends. With my conversations with numerous upperclassmen, I learned that many of them went through the entire recruitment process alone – something I couldn’t imagine doing. Having a group like mine isn’t common, and I’d encourage anyone going through a similar period of time to confide in close friends.

The second refers to conditional happiness, and I’m not talking about the conditional happiness that refers to happiness derived from being better than those around you – although that is definitely a thing (personal satisfaction with your offer). This type of conditional happiness refers to the inability to be 100% happy for someone when you also have skin in the game. I talk about it a bit in episode 12 of Minimally Edited, but I found it difficult to escape an underlying stinging feeling when someone would get an offer before me, even if it was a close friend. My happiness and joy for that person were always accompanied by a thought of damn, why can’t that be me? From what I can tell, this is a relatively common feeling with no true cure – a very human flaw. The only way to feel 100% for someone else is to be removed from the process.

6. Interviews!

The conclusion of info sessions, networking, and applications will hopefully land you a couple of interviews – which everyone says is the hard part. Usually, banks will give a virtual first-round interview with first and second-year analysts from your school. From there, you’ll get an in-person or virtual super day consisting of around four 30-minute interviews. I’ve always considered interviews as a way to show off technical prowess and personality at the same time.

The best interviews stem from a mix of repetitions and excitement. Like anything, getting the reps in for various interview answers can help you refine your responses and deliver better under pressure. The excitement part is similar to that of the networking section. If anything, you’ll have more leeway with excitement levels during an in-person interview with a large age gap. This leads me to probably the single most important thing in recruiting: being liked.

The Likeability Factor

I wanted to coin this term until I found out that Tim Sanders beat me to it about two decades ago with his book, “The Likeability Factor: How to Boost Your L-Factor and Achieve Your Life’s Dreams”. Seems pretty legit. In it, he explores the idea that there are four main elements that comprise likeableness:

Friendliness – your ability to communicate liking and openness to others

Relevance – your capacity to connect with others’ interests, wants, and needs

Empathy – your ability to recognize, acknowledge, and experience other people’s feelings

Realness – the integrity that stands behind your likeability and guarantees its authenticity

Sanders says that boosting these four elements is crucial in improving your likability factor. My approach is similar.

My perspective is based on all the characteristics that make up one’s personality. The impression that you give off in an interview is the combination of traits such as relatability, humor, and authenticity. The key to being likable is finding the sweet spot for each individual trait. If each characteristic is on a spectrum of extremes, there is a smaller sub segment that is optimal, a likability zone if you will.

For example, the sweet spot for relatability is definitely closer to the very relatable side of the spectrum – being more relatable always helps until it seems like you’re trying. Humor, on the other hand, probably has a wider sweet spot that is more toward the middle of the range. The not funny – fears of working with a robot – and the too funny – can’t be taken seriously – sides of the spectrum are dangerous, but anywhere in between from kind of funny to pretty funny is safe. For every personality trait, the goal should be to pinpoint and act within the likability zone.

An additional layer of complexity comes when you consider that every individual’s likability zone varies based on their own personality. This follows the idea that people like other people that are similar to them. Taking these differences into consideration poses a dilemma of sorts that puts people into two camps: (a) you shouldn’t change your personality for other people, it’s important to remain true to yourself and (b) tactically adjusting your personality based on situations and those around you can be extremely beneficial.

Interestingly enough, these perspectives are a direct product of the culture you were born into. This paper from 1997 related personality authenticity to one’s internal cultural norms. Western nations view personality as a fixed entity, giving importance to concepts such as staying true to yourself. In contrast, East Asians saw personality as a malleable entity and adjusting personality traits to be a skill. That being said, my opinion falls under the second group – though possibly because I’m Asian.

Psychologist William Fleeson found that authenticity sometimes comes from acting against your predetermined character traits. In fact, authenticity is consistently associated with extroversion. When an introverted person acts more extroverted in a social setting, they feel more to themselves or authentic. This goes back to the excitement point from earlier. Not only can acting more excited and extroverted enhance the quality of a conversation, but it can also bolster how authentic you’re being.

“Being flexible with who you are is okay. It is not denying or disrespecting who you are. People are often too rigid about how they are and stick with the comfortable and familiar. Adapting to a situation can make you more true to yourself in some circumstances.”

– William Fleeson

Alpha Maximization

We’ve gone over the benefit of coming off as excited and extroverted, but it’s equally important to know when to dial up those traits. I’ll refer to this as maximizing the alpha of your efforts. Across a four-interview super day, for example, it’s important to gauge what kind of personality is interviewing you when deciding when to dial up your excitement – something you should already be doing to boost your likability factor.

The importance of this lies within the structure of interview deliberations. Typically at the end of a day full of interviews, all the interviewers will come together to discuss which candidates they want to move on or give an offer. In that meeting, they'll attempt to rank applicants based on the notes of completely different interviewers – seems pretty difficult. Similar to the benefits of knowing someone on the inside, coming off as more extroverted to an outspoken, personable interviewer increases the probability of them vouching for you behind the scenes. Additionally, if they’re naturally a more extroverted person, their comments will likely hold more weight during deliberations. The untapped alpha lies within the interviewers that will pull hard for you. Swing thought: if they are extroverted, outspoken, or opinionated, crank it up.

I noticed this during an in-person super day I had in New York. Out of four interviewers, one had a particularly extroverted and outspoken personality. After a couple of basic interview questions, he told me directly to stay away from the typical, scripted responses that everyone prepares and asked me what my goal in life was – a pretty worrying situation at the moment. Thankfully, I got lucky. Following my response, which apparently was “the best answer he had heard thus far”, I noticed a tone shift for the rest of the interview. In the end, after flying through the technicals, he concluded by giving me advice for the rest of my interviews, essentially telling me that he believed in me. Although I’ll never know what happened behind the curtains after all the interviews, I assume he vouched for me. After I got the offer, he wrote me an email saying that he was “right to say that I would have done well.”

While this comes in the context of interviews, maximizing alpha applies in networking as well. More outspoken individuals yield higher potential alpha because of their voice in deliberations. I mentioned that landing the interview is often the difficult part, mainly because of the sheer quantity of applicants. Calls help analysts distinguish differences between applicants. When deciding who gets an interview, extroverted analysts will likely pull hard for those that they like.

Calm After the Storm

I’ve learned a ton from the investment banking recruiting process, even outside the scope of answering technical questions. I’ve learned about myself – how I like to work, what motivates me, my strengths and weaknesses. I’ve learned about psychology – trauma bonding, good conversations, personality variances. And I’ve learned about how the world works – the role of luck, personal and professional connections, capitalizing on similarities.

At its core, this piece has been a helpful reflection on a huge part of my short professional life, a time that I’m glad is over. Writing down my experiences has allowed me to consciously think about my big takeaways from recruiting while also creating something that I think will be cool to look back at down the road. On that note, I’m curious how my perspectives on the topics that I brought up change as I grow. Will I alter certain takes after new life experiences?

At the same time, however, I hope you, the reader, were able to get something out of it. If you’re a prospective banker, consider my advice and learn from my experience. If you’ve finished recruiting or want to stay as far away from banking as possible, I hope that I’ve been able to offer a new perspective on topics and intangibles that aren’t typically discussed. At the very least, I hope you’ve enjoyed reading me ramble on about something that I’m passionate about.

🙌

josh i had no idea u were such a talented writer this was crazy insightful. committing to IB early on is a smart move but for sure not without its valleys

i would literally recommend this to anyone thinking about banking or even just deciding on what to major in, i didn't go through the process myself but from what i've heard from all my b-school peers this is a pretty realistic take on playing the recruiting game well. would love to see longer think pieces from you!!